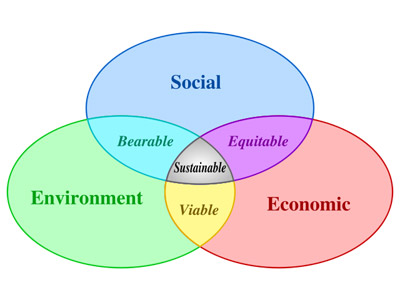

Remember that sustainability is about more than the non-human environment. It's also about the economy and society. In that spirit, I present to you an excerpt of an article from Bloomberg Business Week about the financial crisis by Hernando de Soto in which the author presents a unique perspective on the event.

The Destruction of Economic Facts

Renowned Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto argues that the financial crisis wasn't just about finance—it was about a staggering lack of knowledge

When then-Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson initiated his Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) in September 2008, I assumed the objective was to restore trust in the market by identifying and weeding out the "troubled assets" held by the world's financial institutions. Three weeks later, when I asked American friends why Paulson had switched strategies and was injecting hundreds of billions of dollars into struggling financial institutions, I was told that there were so many idiosyncratic types of paper scattered around the world that no one had any clear idea of how many there were, where they were, how to value them, or who was holding the risk. These securities had slipped outside the recorded memory systems and were no longer easy to connect to the assets from which they had originally been derived. Oh, and their notional value was somewhere between $600 trillion and $700 trillion dollars, 10 times the annual production of the entire world.That's only the middle of the article. For the beginning and end, I recommend you read it in its entirety at the link in the headline.

Three years later there's still plenty to be concerned about. Governments have worked to enact major financial and regulatory reforms, such as the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act ushered through Congress in 2010 by former Senator Chris Dodd (D-Conn.) and Representative Barney Frank (D-Mass.). Dodd-Frank has sought to move derivatives into clearinghouses where more data about them can be collected. It's a step in the right direction. But if you believe in the value of public memory and economic facts, the reforms leave a number of problems outstanding.

First, various groups of derivatives end users, such as nonfinancial companies and sovereign wealth funds, are likely to be exempted from the clearing process—from 40 percent of them, according to Craig Pirrong of the University of Houston's Bauer College of Business, to 70 percent, according to Michael Greenberger, a former Commodities Futures Trading Commission director. Second, the information collected would be available only to regulators because certain business data are considered "proprietary." Third, the $700 trillion worth of derivatives that ignited the recession are not covered by Dodd-Frank. Warren Buffett successfully lobbied for their exclusion, saying it would be tantamount to rewriting old contracts and would force healthy derivatives players such as his own Berkshire Hathaway to post collateral on old deals. Fourth, the clearing system is not likely to be fully operational for another 5 to 10 years. Fifth, many clearinghouses do not have the kind of complete information required by traditional public memory systems: incentives for recording that asset owners can't resist; standard classifications to facilitate identifying and governing the assets; universal access to the information; integration or linkages with other recording systems; provisions to protect third parties from negative externalities; identification of all asset holders and interested parties; limited liability provisions to improve accountability.

That's a lot of failure to digest in a single paragraph. So let's look sector by sector at the sorry state of facts in the financial system.

Maybe the legislators and regulators will listen to what de Soto wrote.

No comments:

Post a Comment