I concluded 'Snowpiercer', by quoting the following transition and commenting on it.

Follow over the jump for Ellid's take on Ayn Rand and "Atlas Shrugged."There is one thing that's puzzled me, though. Some reviews, including several raves, have claimed to see the influence of a writer who is about as far from Occupy Wall Street as it's possible to get. Despite the political allegory, the very clear parallels to modern life, and the criticism of elitist greed that permeates the entire film, a handful of people are convinced that Snowpiercer was at least partially inspired by the least liberal, least likely of writers: Ayn Rand.That sets up part two, in which Ellid descended from the sublime to the ridiculous. Stay tuned.

Yes. Really.

And now, the rest of Books So Bad They're Good: Objectifying the Apocalypse.

Ayn Rand is a true giant of contemporary culture. Her influence upon modern political and economic thought, especially on the Right, is undeniable. Rep. Paul Ryan, the fitness fanatic who ran for the Vice Presidency two years ago, reportedly used to require his interns and staffers to read her books, while Sen. Rand Paul, son of ur-Libertarian Ron Paul, might even have been named for her. Her books sell in the millions, her followers spend huge sums of money to send educational materials about her writings to public and private schools, and her beliefs about the morality of unrestrained laissez-faire capitalism and the evils of a social safety net have become commonplaces in current discourse. Her works have never been out of print, and her beliefs, called Objectivism for their alleged reliance on objective rather than subjective thinking, are a quasi-religion to her avowedly atheist followers.As I wrote three years ago, Collapse is all there in the Objectivist manual.

For all her popularity among American conservatives, Rand’s thinking was shaped far more by her early life in Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union than anything she picked up on this side of the Atlantic. Born in 1905 to a secular middle-class Jewish family in St. Petersburg as Alisa Zinov’yevna Rosenbaum, the future Ayn Rand started writing before her tenth birthday, possibly because she found school boring even though she attended a prestigious gymnasium where she rubbed shoulders with the likes of Vladimir Nabokov’s younger sister. She believed in republican government then, and was thrilled when Alexander Kerensky’s provisional government overthrew Tsar Nicholas II when she was twelve.

Alas for Alisa Rosenbaum and her family, Kerensky was in turn overthrown by Lenin and the Bolsheviks in October of 1917. The family pharmacy was confiscated by the new regime, and the Rosenbaums fled to the Crimea for several years. They returned to St. Petersburg/Petrograd/Leningrad in 1921, where they nearly starved thanks to anti-bourgeois sentiment. Alisa nevertheless managed to enroll in Petrograd State University, where she survived a purge of bourgeois students and was allowed to graduate in 1924. After a year’s study at film school, she decided that a) she would be a writer, b) she would call herself Ayn Rand (“ayn” from the Hebrew word for “eye,” “rand” possibly as a shortened version of “rosenbaum”), and c) she was sick and tired of the Soviet regime.

She applied for a travel visa to visit American relatives and left the Soviet Union permanently in January of 1926. Reportedly she was so moved by the sight of the clean, uncluttered lines of Manhattan’s skyscrapers that she burst into tears, which is a lovely story until one realizes that the tallest skyscraper at that time was not the gleaming Art Deco wonder of the Chrysler Building or the hulking pillar of the Empire State Building, but the fussily turreted Neo-Gothic Woolworth Building.

Regardless, Rand soon left New York to live with relatives in Chicago, where a relative who owned a movie palace let her watch all the films she wanted at no cost. After a few months she left for California, where she eventually managed to land a job as a film extra and sometime scriptwritern for Cecil B. DeMille. She also married an actor named Frank O’Connor, which took care of any possible issues related to her visa (which should have been time limited), and was able to become an American citizen in 1931.

Soon after becoming a real, true, live American, Rand started selling plays, scripts, and novels. With the exception of a play called Night of January 16th, a legal drama that picked a “jury” from the audience each night, none of these projects was all that successful – her first novel, We The Living, was published in 1936 and went out of print soon thereafter – but Rand was convinced of her own talent and determined to succeed.

Along the way Rand became active in Republican Party politics, campaigning for Wendell Wilkie in 1940 and becoming friends with Austrian economists Ludwig von Mises (who called her “the most courageous man in America,” and no, that is not a misprint) and journalist Henry Hazlitt. By the time her next novel, The Fountainhead, came out in 1943, Rand was thoroughly convinced that free market capitalism was the only moral economic system and laissez-faire politics the only moral system of governance, and used the book as way to put her beliefs before the public.

This was not nearly as easy as it sounds; The Fountainhead, which tells the story of a dedicated architect, the woman he loves (and may or may not have raped), and the housing project he blows up rather than let his plans be altered in any way, shape, or form, was rejected by twelve publishers before finally being accepted by Bobbs-Merrill. The editor who bought the book, Archibald Ogden, was so convinced that the book was worth publishing that he threatened to quit if his superiors didn’t publish it, and their trust in him and his judgment was richly rewarded. The Fountainhead was a smash hit despite that pesky little conflict called World War II, and Rand not only found herself financially secure for the first time since the Bolsheviks appropriated her father’s business, but was in demand as a screenwriter and script doctor in Hollywood.

This in turn led to Rand becoming involved with anti-Communists in Hollywood, writing essays and articles on their behalf, and eventually testifying as a friendly witness before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947. Her subject was the profound difference between her personal experiences in the Soviet Union and the way the USSR was portrayed in the 1944 film Song of Russia, never mind that a) the film was a forgettable bit of wartime propaganda about an ally and b) she hadn’t set foot in the USSR in over twenty years.

She also tried to warn HUAC about the Communistic, anti-business strain in the 1946 film The Best Years of Our Lives but was not allowed to bring it up. This may be why she later dismissed her testimony as useless, although she likely was quite pleased by the subsequent Red Scare and Hollywood blacklists.

Another disappointment was the 1949 film adaptation of The Fountainhead, which starred a badly miscast Gary Cooper, a semi-deranged Patricia Neal, and the riding crop Neal uses to beat Cooper. Rand hated the film with the hate she normally reserved for Communists and New Dealers, even though she’d written the bulk of the screenplay and thus should have known what was coming. That the film has gone down in Hollywood history as a heavy-breathing camp classic probably did not please her one bit, although it’s provided laughs for generations of bad film fanatics.

By the early 1950’s Rand had given up on Hollywood and moved permanently to New York. The Fountainhead may have flopped as a film, but the book had been so popular that Rand had received a steady stream of thoughtful, laudatory fan letters. Many of these fans gathered around Rand in New York, where they soon called themselves “The Collective” as a joking nod to the Communism regime she’d escaped via the harrowing process of getting a visa and sailing to New York. Members included future Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan, a young married couple, Nathaniel and Barbara Blumenthal (later “Branden,” which combined “Blumental” and “Rand”), and Barbara’s cousin Leonard Peikoff.

These bright young people were the very first audience for Rand’s next book, 1957’s Atlas Shrugged. This huge, dense, all but impenetrable book was intended as a summing up of Rand’s beliefs in unrestrained capitalism, unrestrained self-interest, and unrestrained wealth creation. She called this new philosophy “Objectivism” because of its belief in unrestrained secularism rather than intuition, instinct, or revelation, and held that it espoused:

“the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his own only absolute.”

Alas for Rand, this grand-sounding rehash of Aristotle, Nietzsche, and Social Darwinism was handicapped by overblown prose, characters with the depth of toilet paper, a ludicrous plot involving adultery, a transcontinental railroad, a super-metal, the evils of state assistance for the needy, some extremely short-sighted futurism, and a whole lot of high-falutin’ speechifying in place of dialogue. People (usually very bright, or very disgruntled, or both) start to disappear, characters with names like "Francisco Domingo Carlos Andres Sebastian d’Anconia," "Dagny Taggart," "Midas Mulligan," "Wesley Mouch," and "Ragnar Danneskjöld" cavort across the pages (and frequently into and out of each other's beds, marital status notwithstanding), and society collapses with surprising swiftness.

The entire mess, which is 1,200 pages of tiny little type in trade paperback, culminates in one of the most astonishing passages in world literature, in which the inventor John Galt, who’s managed to “sto[p] the motor of the world” by persuading the most creative thinkers, industrialists, and artists to withdraw completely from society into a free market laissez-faire paradise, delivers a fifty-plus page radio speech setting forth his reasons for basically trashing the social compact and bringing about catastrophic economic failure. This speech, which by some estimates would take several hours to deliver, not only doesn’t lead to an epidemic of narcolepsy among bored listeners, but is received with hosannas by ordinary citizens and becomes the catalyst for a Utopia based on Objectivism.

The parallels to Snowpiercer are obvious even to a mole.

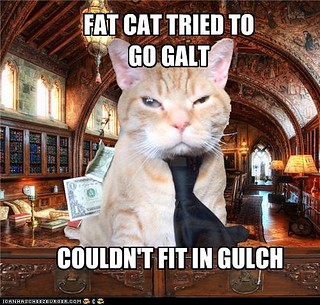

Much to Rand’s surprise, the book was slammed by critics on the Right (notably by anti-Communist stalwart Whittaker Chamber, who wrote a brilliant takedown called “Big Sister Is Watching You”), the Left, and everyone in between who liked good writing, sharp characterization, and a plot that made sense. Rand, worn out by the lengthy writing and editing process (not to mention an affair with Nathaniel Branden, which took place with the full knowledge of her husband and his wife), fell into such a deep depression that she never wrote another novel, and who can blame her? If anyone deserved to “go Galt,” it was her.

Alas for literature, neither critical Bronx cheers nor its author’s personal drama had the slightest effect on sales. Atlas Shrugged was a huge financial success, with international sales in the millions. Rand roused herself from her post-Atlas torpor long enough to give an interview to Mike Wallace of CBS where she modestly claimed to be “the most creative thinker alive.” She then embarked on a long, extremely successful career writing and lecturing about Objectivism around the United States, including appearances at prestigious colleges and annual speeches at the Ford Hall forum.

That these public appearances were riddled with contradictions didn’t seem to bother her or her followers one whit; if Ayn Rand wanted to oppose the Vietnam War while condemning draft dodgers as “bums,” or deemed homosexuality “immoral” and “disgusting” while calling for the repeal of all laws criminalizing it, that was solely because she based all her thoughts and actions upon objective thinking and moral clarity. She also had no trouble endorsing Republican hard-liners like Barry Goldwater for President, dubbing the Yom Kippur War a conflict between “civilized men” and “savages,” or approving of Europeans seizing land from Native Americans. Self-interest über alles evidently applied to politics and social movements just as much as it did to the making of money.

Rand’s later years were marred by personal strife (former boy toy Nathaniel Branden’s marriage blew up in 1968, leading to him and his wife being expelled from the Collective, whereupon he promptly accused Rand of promoting a personality cult), the loss of her long-suffering husband in 1979, and a bout of lung cancer thanks to years of chain smoking. Her nadir probably came in 1976, when financial problems stemming from her cancer treatment forced her to sign up for “government charity” in the form of Social Security and Medicare.

Ayn Rand died in 1982 of heart failure, leaving behind several overblown books, the grieving remnants of the Collective, and a funeral that was graced both by Alan Greenspan and a six-foot floral arrangement shaped like a dollar sign. She was buried in a cemetery in, I kid you not, Valhalla, New York, and left her entire estate to Barbara Branden’s cousin Leonard Peikoff. Her influence has only continued to grow since her death, as anyone who remembers the brief vogue for “going Galt” a few years ago will recall, and even though no less a Randite than Alan Greenspan admitted that his Objectivist-inspired management of the economy was a big, fat, flop, her ideas keep returning like a particularly vicious type of bloodsucking undead.

Then again, the popularity of Rand’s works, especially among Tea Party favorites in their 40’s and early 50’s, should not surprise anyone. As John Rogers put it so eloquently,

“There are two novels that can change a bookish fourteen-year old’s life: The Lord of the Rings and Atlas Shrugged. One is a childish fantasy that often engenders a lifelong obsession with its unbelievable heroes, leading to an emotionally stunted, socially crippled adulthood, unable to deal with the real world. The other, of course, involves orcs."

%%%%%

Have you ever read Atlas Shrugged? Worked for Paul Ryan? Would you admit it if you had? Seen the numerous and obvious parallels between Snowpiercer and the saga of John Galt? Now’s the place to exercise your moral clarity and come clean….

No comments:

Post a Comment